By P. Paolo Maria Siano*

Peter Stiegnitz (Budapest 1936 – Vienna 2017), a Jew who survived the Nazi persecution and emigrated to Austria in 1956 in the wake of the Hungarian Uprising, was a writer, sociologist, ministerial official of the Federal Press Service in the Austrian Federal Chancellery and, finally, a visiting professor at the University of Budapest. In 1970, Stiegnitz was initiated as a Freemason in the Vienna Lodge Humanitas, which belongs to the Grand Lodge of Austria (GLvÖ). [Richard Nikolaus Eijiro, Count of Coudenhove-Kalergi belonged to that Lodge as well.]

He belongs to other lodges of the Grand Lodge, among them for 30 years the Wiener Lodge, Zum raue Stein. Stiegnitz also holds Masonic offices at the management level of the Grand Lodge. As Grand Chapter Master, he has been the head of the York Rite for 10 years, which, with the Old and Recognized Scottish Rite, is one of the high-grade systems of the Masonic Masters of the Grand Lodge. On February 2, 2017, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Austria, Georg Semler, stopped at the grave of "Brother" Stiegnitz, in the presence of numerous Freemasons, gave a funeral speech in which he described Stiegnitz as "a great of our covenant," as reported by the very well-informed Masonic website Freemason-Wiki.

Grand Master Semler is the same one who, together with Monsignor Michael Heinrich Weninger, priest of the Archdiocese of Vienna and member of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, presented his book in Vienna, which was approved as a doctoral thesis at the Pontifical Gregorian University. In it, Weninger expresses the hope for a reconciliation between the Church and Freemasonry. As I wrote on this page on February 27, 2020, Monsignor Weninger belongs to the regular Austrian Freemasonry, which is connected with the English Freemasonry of the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE).

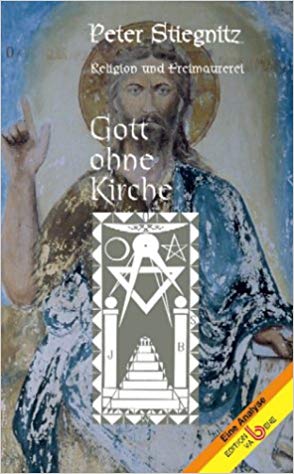

Now I would like to draw attention to a book that allows us to explore the nature of today's Austrian Freemasonry: "God without Church: Religion and Freemasonry", Edition Va Bene, Vienna-Klosterneuburg 2003. The author of the book is Peter Stiegnitz.

In the foreword, Michael Kraus, the grand master of the Grand Lodge of Austria, praises the book in Masonic terms and defines it as "an important and important building block" (p. 9). Kraus enthusiastically mentions the post-conciliar dialogue between Cardinal König and the deputy grandmaster (later honorary grandmaster) of the Grand Lodge, Kurt Baresch (1921-2011). Masonic Wiki informs that Baresch was a former SS officer, psychologist (from 1948) and Freemason (from 1961).

It is a strange union of opposites: in the same grand lodge we find a Jew and a former SS officer. Reconciliation and forgiveness?

Let us return to Grand Master Kraus, who admits that there is the Cantic Enlightenment in Freemasonic thought (p. 10). Kraus declares that he belongs to a Catholic family and expresses the hope for cooperation and harmony between Freemasonry and the Church. He also believes that Stiegnitz's book will help Freemasons and "Profanes" to free the way from of the ballast (p. 11). As we shall see, the "ballast" which Stiegnitz casts away, of which it is necessary to free himself, is unfortunately the entire Christian dogma!

Stiegnitz praises the Enlightenment (p. 18), accuses religious monotheism of intolerance towards polytheistic cults (p. 19) and attributes a human and psychological origin to religion, including the Christian Catholic: it is only a human self-liberation from those needs that cannot be accomplished on its own (p. 32-33).

For Freemasons, the Bible is an ethical symbol. It is not history, but an allegory. Stiegnitz says that pantheism offers the "laicist" Freemasons the way to an acceptable religiosity ... Religiosity is only self-therapy and the Great Builder of the Universe is a symbol of the psycho-spiritual hierarchy (p. 34). Stiegnitz explains that the religious world of Freemasonry, in contrast to religions, is "on the other side" (p. 42-43). Stiegnitz shows sympathy for cantic thinking (p. 50). Stiegnitz also states with regard to the "Christian" or Templar high degrees that the Masonic symbols have no religious but an ethical meaning (p. 57). Stiegnitz clearly writes that the god of monotheistic religions is not good, does not forgive (literally he "is not kind"), since he above all likes to punish. Stiegnitz cites the case "Sodom and Gomorrah" (p. 72) as proof of these statements. Stiegnitz, on the other hand, praises Heraclitus's philosophy that God is harmony of all opposites ("without war there is no peace, without night there is no day ..."). Heraclitus also calls God logos or universal reason. "In Masonic philosophy, the heraclitarian unity of opposites is understood as totality" (p. 81).

Stiegnitz also likes Spinoza's thinking. Stiegnitz knows that Spinoza is a pantheist who believes that nature is divine and identifies God with nature. Stiegnitz explains that the Masonic religiosity and Spinoza's philosophy have in common the connection – or invocation – to an impersonal divinity ("Here we already experience decisive approaches of masonry religiosity: invocation of an unpersonified God," p. 97) Like Freemasonry, Spinoza also attaches great importance to ethics. Stiegnitz states that Spinoza thought like the Freemasons and the Freemasons think like Spinoza ("Spinoza thought Freemasonic, Freemasons think spinocaic", p. 97).

Stiegnitz also expresses sympathy for the thinking of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), a Hegelian, atheist and materialist. Stiegnitz writes: "The religious (self-) understanding of Freemasonry is reflected above all in the cross-connection of theology to philosophy in the sense of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872)," (p. 118). Even for Feuerbach, the philosophy of religion has no place in heaven, but down here, here it is theology of the senses (p. 118). In Freemasonry, religious and Christian ties (e.g. "Christian" high degrees) are neither dogmatic nor confessional. Stiegnitz presents Feuerbach as a "brother without an apron" or as a man who was not initiated into Freemasonry, but thought like a Freemason.

According to Stiegnitz, Feuerbach is also close to Freemasonry when he separates Christianity from the Pauline "Jesuism" (Jesus) and presents humanity from down here (p. 118-119). Feuerbach cannot bear the institutional and dogmatic religion. Later Sigmund Freud will also say that religion is the illusion of man (p. 119). According to Stiegnitz, it follows that atheism (especially Marxist) does not arise in opposition to religion, but in contrast to clericalism.

To prove this, Stiegnitz says that there is no atheism in oriental beliefs such as Buddhism and Hinduism (p. 129). The young Feuerbach had represented a religion without theology, an intimate and religious need for something, without being bound by confessional teachings. Thus Stiegnitz shows that he prefers this anthropocentric "path" to the Divine without popes and without priests. This religiosity without theology and without dogmas is the way that characterizes the attitude of Freemasonry towards religion (p. 144). Stiegnitz describes Feuerbach's attitude to religion as "early Freemasonry" (p. 144).

In summary, we can also take account of the clear anthropocentrism and immanentism in the thinking of "Br." Stiegnitz (head of the Austrian "Christian" or "Templar" Freemasonry of the York Rite), whose book was praised by the then Grand Master of the Grand Lodge Michael Kraus, does not share the optimism of the current Grand Master Semler and Monsignor Weninger regarding a real reconciliation between the Church and the Austrian Freemasonry (GLvÖ) associated with the UGLE.

* Father Paolo Maria Siano is a member of the Order of the Franciscans of the Immaculate (FFI); the doctor of the Church is considered one of the best Catholic connoisseurs of Freemasonry, to which he has dedicated several standard works and numerous essays.

Translation/footnotes: Giuseppe Nardi

Picture: Wikicommons

Picture: Wikicommons

No comments:

Post a Comment